Old Adelaide Gaol Stories

A Visit to the Adelaide Gaol – 1939.

Behind Prison Walls. 1939.

On Saturday morning I found myself the possessor of a pass of admission to His Majesty’s Gaol Adelaide. My companion was Miss Sylvia Cowles, an English visitor who for the past 13 years has been a voluntary handicraft instructress to the women in Holloway Prison, London, and who during her world tour has inspected many women’s prisons in America and Australia. Miss Cowles will return to England in the Orion on Thursday.

It was interesting and gratifying to learn that the daily average number of women prisoners for the whole of the state, except in cases of a few days confinement in country gaols, all the women are housed at the Adelaide Gaol, is the lowest on record being a daily average of 6.

It was also interesting to hear from Matron Hogarth who has been in charge of the women for the past 10 years, of the hygienic changes in the regulation clothing during her term of office, and the present uniform Is far removed from the conception which the majority of people have of traditional prison clothing. It is both attractive and serviceable, the blue frocks well made in a coat style, by the tailors imprisoned at Yatala, stitched hats to match, fawn stockings, and tan shoes, also made at Yatala, of a type which many a woman golfer or hiker would find very useful and acceptable in her wardrobe.

A moments comparison with the old time clothing, of which samples are still to be found in the prison storeroom, ungainly full skirted dull blue frocks and unattractive sunbonnets, white cotton stockings, and black blutcher boots, will suffice to show that restoration of self respect is much easier for the women prisoners of today than it was in the past. Every woman knows the telling effects of clothes on her outlook on life.

The bathing arrangements too have undergone a change, and the old thick slate slab bath in the open courtyard, which has given place to spotless bathrooms with hot water heaters, still stands as a reminder of days gone by. Bedsteads have replaced hammocks in the cells. Prisoners may borrow from the library reading material for their leisure hours, in the winter they may sit by the fire at certain hours in the sewing room with their embroidery or knitting, and in the summer they may tend the flower garden which borders their courtyard.

Sweet smelling violets greeted us on Saturday and some new antirrhinum plants sent in by a discharged prisoner who wished to provide for a further colourful corner, were gaining the special attention of one of the women.

There is a group of three women who now visit the Adelaide Gaol regularly. Two teach the women prisoners handicrafts, and the third is concentrating on reorganising the garden. Knitting is the chief occupation of the handicraft workers, who are with the prisoners every week, and wool is donated by the workers themselves, and their friends.

They have no organised committee, prompted by the thought that the days must seem long to the women inmates and their interests must be few, the three women approached the gaol authorities and tried out a day’s experiment. It seemed to fill such a need that they have continued with the work and are planning to make the recreation room brighter and provide some comfort for the hospital ward. Now that the handicraft workers are known, the afternoons they have with the prisoners are developing into happy meetings. The matron assists, and all knit together, it resembles quiet a little social meeting.

Acknowledgement: The Advertiser. 28 March 1939

James Albert Coleman – Executed 2 July 1908

Adelaide, South Australia 1908

“Coleman, how do you plead, Guilty or Not Guilty for being intoxicated in a Public place?”

”Sir, I am not guilty! I do not deserve this kind of treatment.”

”Mr Coleman you were found drunk in a public place and Constable Ring has arranged for you to appear in court tonight so that you may take your fishing cutter out on tomorrow’s early tide. I find you guilty.”

“The fine is five shillings or 7 days imprisonment for non payment.”

”Very well, here is the five shillings. I still say I don’t deserve this. I have been a resident here at Glenelg for 50 years and have not been in any trouble before.”

James (Joe) paid the fine then headed to the Pier Hotel across the square where he began consuming whiskies and telling anyone within earshot what had happened and that he would later fix things.

Coleman then made his way to his home in Reid Street, a small lane off High Street.

On entering, he told his wife that she would soon be a widow as he was going to shoot himself. His wife already knew about his scrape with the law as she had earlier met Mr Hicks, a Justice of the Peace, who had fined Coleman. Hicks had said “Try and take him home.” but of course she could not at that time.

Coleman then took out his old muzzle-loading rifle and started to load it. His wife tried to prevent him and a struggle ensued. In the struggle she managed to wrest the ramrod from him. Coleman pushed her aside and went out into the street.

He knew that it was Constable Ring’s practice to meet the last two trains from the City to Glenelg, at Millers Corner, which was the junction of Jetty Road and Partridge Street and Rudolph Street (now Gordon Street).

Coleman knew that Constable Ring would be standing outside the Terminus Hotel at 11.00pm. He proceeded to walk up and down the footpath in an agitated state.

Mr Ranford, who was acquainted with Coleman; asked him what was wrong.

Coleman replied, “That – Ring shot me in today. Revenge is sweet. I am going to shoot him and then myself. Life is nothing to me.”

Charles Ranford tried to talk him into going home, but Coleman would not listen.

The last train was just crossing Brighton Road and entering Jetty Road at a few minutes past midnight. Coleman stepped out into the road. Constable Ring saw Coleman and he also stepped out into the road.

Ring said “What have you got there, Joe?”

Coleman’s answer was not heard due to the noise from the approaching train.

“You had better go home Joe.” Constable Ring saw that the train was nearly up to where they both stood. Constable Ring said, ”Look out, Joe!” to try and distract him.

At that instant Coleman raised the rifle to waist high and fired. Constable Ring staggered back and fell to the ground. He then raised himself to a standing position then fell forward, lifeless.

A Mr McCaffrey who witnessed the incident turned and ran to the police station in Mosely Square.

Mr Ranford bent over the Constable and then said, ”Someone go for the doctor!”

Meanwhile, in the excitement, Coleman started running from the scene, down Partridge Street and into High Street, not to his home but in the direction of Mosely Square.

Mr McCaffrey, on reaching the police station, found it unattended. He then informed the Glenelg Station Master what had happened and asked him to contact the Adelaide Police.

By this time, Coleman was opposite the police station knocking on the door of the Pier Hotel with the intention of obtaining a drink. The manager came to the door and told him to go away. Coleman began pacing up and down the footpath.

A Mr Ross, who knew Coleman, saw him and walked over to him and said, “Joe, Constable Fitzgerald is looking for you.”

Coleman replied, ”I am in trouble.”

They both sat down on a seat and spoke briefly. Mr Ross then left and headed towards the police station. Coleman started walking towards the jetty and, on reaching a point half-way along, threw the rifle and powder flask into the sea. He then disappeared into the night.

The City police arrived on the scene a little later and began interviewing witnesses.

A search was organised and the police began searching the side streets and along the jetty, but Coleman was not to be found. The police then placed men on surveillance at Coleman’s house in case he returned that night. In fact, it would be several weeks before Coleman was apprehended.

The shooting had occurred at a few minutes past 12 on the Saturday night.

On the Monday afternoon, the Coroner, doctor Ramsay Smith held an inquest into the death at the Glenelg Town Hall.

William Fitzgerald, foot constable, stated that he identified the body of Constable Ring and that he last saw him alive at 11.00pm on the Saturday evening. At approximately 12.05am he heard a gunshot report from the direction of Millers Corner so he hurried towards the scene. On reaching it he saw constable Ring lying on the ground.

Mr Fisk, who was already present at the scene said, ”Someone has shot your mate.”

The constable then began enquiring into what had happened. Ring’s body was then removed to the morgue.

Constable Fitzgerald said he then went back to the station to get a revolver and on doing so he then set about looking for Coleman.

The Coroner then went into great detail asking why Constable Ring was not armed. He asked Detective Fraser, ”On what occasions are police supposed to carry firearms? I thought mounted police are always to carry a firearm. ls this not so?”

Detective Fraser replied, ”Yes, this is so. Constables on night duty normally do.”

The Coroner said, ”This is a most important matter. When was the constable supposed to have carried a weapon?”

Detective Fraser replied “There is no regulation compelling him to carry one.”

The Coroner said he thought it would be difficult to find a case in which there was less conflict of evidence than in the present one. The facts seemed to be clear as regards to Coleman’s actions in the death of Constable Ring.

The Coroner, Mr Ramsay Smith, then went on to say there were two things which demanded some remarks because of two unsatisfactory circumstances. If they had not existed then the life of the deceased may not have been taken.

The first was the question of the police being able to defend themselves. The function of the police was to prevent crimes and to see that the peace was kept. A policeman could not do that if he were dead. If he was expected to do his duty, then he should have the means of protecting himself and the lives of others.

The evidence was quite clear that Constable Ring knew of Coleman’s intentions with the rifle and was taking steps to get the gun from him. If Ring had been armed then the affair might have taken a different turn.

Mr Ramsay Smith said he was quite aware of all the objections that were brought forward against entrusting police constables with firearms but if a man was not fit to be entrusted with firearms then he was not fit for the police force.

“In these days when criminals seemed to hold the lives of honest people and police officers so cheaply there is too much sentiment and too little firm dealing with the criminal population.”

That led him to the second point, which was the amount of consideration shown for offenders and criminals.

The deceased put himself out by arranging for the offender to have the drunk case heard before the Monday so that the offender could go fishing on the Sunday morning. It would have been better to keep him locked up until the Monday morning and then brought into the Court.

After hearing further remarks, the Coroner said there was a case for indictment of wilful murder by a man known as Joe Coleman and then issued a warrant for the arrest of Coleman.

The next day, Tuesday, the body of Constable Ring was conveyed to the Payneham Cemetery.

It was estimated that at least 10,000 people saw the procession as it went between Glenelg and Payneham. Shutters were up on premises and flags were half mast along the route. The funeral left Glenelg at 1.30pm and on arrival at West Terrace, the procession was joined by 100 foot police and 20 mounted troopers.

The cortege then went via Sturt Street, then to Gouger Street and into Wakefield Street. There, outside the Fire Station, the firemen were all lined up as a guard of honour.

In the procession was the Chief Secretary and the Police Commissioner, Colonel Madley.

As the cortege passed Queen Victoria’s statue, the Mayor of Adelaide stood with Aldermen and Councillors.

The cortege then went down Hutt Street to the Botanical Gardens gate where the cortege disbanded, the hearse moved on towards the cemetery. Foot police and mourners then boarded the special trams to take them to the cemetery where the service commenced at 5.00pm.

The service was conducted by Reverend George Raynor of the Glenelg Congregational Church. The police band played solemn music, one item being “Go bury thy sorrow”.

Meanwhile, Coleman was still at large.

The police had been searching the fishing boats, believing that Coleman might try to sail to Kangaroo Island where he did most of his fishing and consequently knew the Island very well.

A search was made of the sand hills on the north shore and along the sand hills towards Brighton. Sightings were reported to police during the week that he had been seen in the Reynella and Morphett Vale areas. Police parties began scouring the district making the Crown Hotel their nightly sleeping quarters.

A Mr Forsyth of Morphett Vale reported that a man called at his house asking directions and seeking water. He told police he was sure it was Coleman whom he had known at Glenelg 25 years ago.

Many of the sightings of Coleman during the previous two weeks proved to be true. He had been seen at a distance quite often, but by the time the police were contacted he had moved on. One woman had said that one morning she saw Coleman filling a can at her rainwater tank.

The chase was well attended by newspaper reporters from the City papers. Reporters often shared rooms with the policemen and accompanied them in their search for the fugitive.

One morning, two weeks after Coleman’s flight, the police formed a large ”dragline” of searchers starting from the foothills at O’Halloran Hill and stretching as far as Brighton.

The line advanced north towards the Bay Road.

Detective Nettle and Constable Deacon were walking along the Sturt Creek near the Bridge on Morphett Road when they came across a swag on the bank of the creek. About 50 yards away they saw a man reclining on the bank looking in the opposite direction to them. They quickly walked up to him.

Constable Deacon said, ”Hello, old fellow. What are you doing here? Aren’t you Coleman?”

Coleman replied ”Yes” then changed his answer to ”No”.

Detective Nettle said, ”Whether you are or not, you are coming with us.”

The detective told him to roll up his trousers above the right knee and saw the name J.A. Coleman tattooed on it. They then inspected his swag and in it found several fowls.

The police then took Coleman to Mrs Coles’ house on the Bay Road and rang the city office advising that Coleman was in custody.

Coleman was then transported to the City watch house where he was cleaned up and given fresh clothing. He had been on the run for two weeks and was in bad condition. Coleman said he had been reading about the police search in the newspapers.

While being washed at the watch house, a small cut was found on his left arm. Coleman said that he cut himself whilst carving his initials on a tree on the banks of the creek and that he had hoped he would bleed to death.

June 1908; James Albert Coleman stood in the dock at the Criminal Court before Mr Justice Homburg, charged with having wilfully murdered Constable Albert Edward Ring at Glenelg on March 29th.

Asked how did he plead, he replied ”Not guilty”.

The Crown Prosecutor, Mr C.J. Dashwood, then opened the case for the Jury.

Mr C. Muirhead and Mr H. Solomon appeared for Coleman.

The court was told that Coleman was arrested by Constable Ring on the Saturday at 2.30pm on the 29th of March. At 9.00pm Coleman was taken before the Justice of the Peace Mr W.M. Hicks and fined five shillings. He was brought before the court that night out of consideration so that he could leave in his fishing boat the next morning.

The Crown produced a diary kept by Coleman and several extracts were read to the court; one that he had been as far as Aldinga in his flight and the other that he had no sorrow for Ring.

Witnesses for the defendant said that Coleman was a solid citizen and was never in trouble with anyone. The Justice of the Peace who had fined Coleman said he had spoken to Coleman later that evening before the shooting and had told him to go home with Mrs Coleman who was there outside the Pier Hotel.

The accused said that he did not blame him (Hicks), that it was Rings fault. “I will shoot him. He has insulted me. I’ve been a resident of Glenelg for 30 years.”

Other Crown witnesses were put on the stand to tell their version of the night’s events. The Judge asked a witness if he thought the accused was insane?

The witness replied, “No.”

His Honour then asked Mr Muirhead, ”Do you suggest that the accused was out of his mind?”

Mr Muirhead replied, ”Undoubtedly, your Honour.”

The Crown was told that the rifle was recovered on the 31st of March and that on April 6th the powder flask. Both were recovered from where they had been thrown from the Jetty into the sea by the accused.

The Crown Solicitor in his address said there were only two excuses; there could be no justification raised for the committal of the fatal deed. One was that the shooting was accidental, and the other that the accused did not know what he was doing. Drunkenness was only an excuse. The accused said he was going to shoot Ring and he did.

The defence brought in Sir James Boucaut as a character witness. Sir James told the court that Coleman had often worked on his boat and that he had never seen the accused in an intoxicated state and had never had any trouble with him.

The Judge in his summing up of the case mentioned the diary extract that said “I have no sorrow for Ring,” and that he deliberately set out to shoot Constable Ring and had done so.

The Jury was retired, returning within 30 minutes with a verdict of Guilty.

When Coleman was asked if he had anything to say, he said, “If the front part of the book was read, it would say ‘to think I have done such a thing as to shoot my friend Mr Ring’. Only the two worst parts were read. The whole lot should have been read. I have nothing more to say, and no excuses to make. I say as I said before, I was not responsible for my actions. My mind seemed a blank. At the present time I can hardly realise it yet.”

His Honour then sentenced the prisoner to death; “The sentence of the court is that you be taken hence to the place from which you came, and there be hanged by the neck until you are dead. You will be buried within the precincts of the Gaol and may God have mercy on your soul.”

The accused did not flinch when the sentence was pronounced and, as he was being taken from the dock, turned to the gallery and waved his hat.

Joe Coleman’s execution was set for 28 days from the day of sentence. Appeals were submitted by his solicitors during this time, but the authorities were unyielding. The law was taking its course.

During this period, a rally against the execution was organised. Several thousand people assembled at Queen Victoria’s statue in Victoria Square. Speeches were made that a new trial should be held or Coleman given a reprieve from hanging.

Rallies and demonstrations were also held at the Grote Street fish market and outside the Advertiser newspaper office.

One night a deputation of 300 people waited outside the Conservatorium on North Terrace for the acting Premier, Mr Kirkpatrick, to emerge, in the hope they could present a resolution adopted by the crowd at an earlier meeting. Mr Kirkpatrick said he could not alter an Executive Council decision, and that they should present it to the Governor.

The crowd reformed at Government House, only to be denied admittance by the police on duty at the gates.

It was reported that Coleman, in custody at the Adelaide Gaol, was perfectly resigned to his fate and was quite prepared to face death.

Coleman’s wife was a regular visitor. His last meeting with her was on the night before his execution.

Coleman was confined to the condemned cell and taken to a small yard for daily exercise. He was watched constantly by warders 24 hours a day.

On the evening prior to his execution, communion was given to Coleman and his wife.

That evening he was removed from the condemned cell to a cell on the first floor of the New Building at the far southern end of the cell block. Prisoners who had occupied the block until that evening were all placed in various other parts of the old section of the Gaol.

Once the door of the cell was closed on Coleman preparations were made on the gallows, which was only a few paces from the cell occupied by the prisoner. He was watched constantly by a warder in an adjoining cell from which had a small section was cut out of the wall for this purpose.

Whilst in the cell that evening, Coleman wrote several letters and a statement which he gave to the Reverend W. Clark, the statement to be read after his death.

At 7.55am the next morning, Coleman’s arms and wrists were secured to a belt placed around his waist and he was brought out of the cell. Official witnesses to the execution were lined up along the rails just back from the trapdoor. Coleman was placed over the trap, facing south, looking towards the large windows.

While the minister read the sermon, Coleman’s feet were strapped together. The rope was then placed on the left side of his neck with the knot placed where the jawbone meets the ear. A hood was placed over his head. The executioner then stepped to an adjacent cell where the lever was situated and, on a signal from the Sheriff that all was ready, the lever was pulled.

The body dropped the required distance then came to a sudden halt throwing the head to one side and enabling the spinal column to be separated at the neck. Death was instantaneous.

The body was left hanging while the official party adjourned back to the office. After one hour the body was laid out and an Inquest was conducted by the Coroner as to the cause of death of the prisoner.

The Coroner, Mr Ramsay Smith questioned the Sheriff extensively on whether the rules in accordance with the law had been carried out. The Sheriff replied that they had.

Joe Coleman’s body was then taken for burial along the north east laneway between the inner and outer walls of the Gaol. Coleman’s last statement that he had given to the minister was read.

“I am deeply sorry for the deed which I committed and face-to-face with death, I can truthfully say that if I had not been mad with drink. I would not have dreamed of shooting poor Ring as we were always good friends. I only knew what I had done when I was told afterwards. I wish to thank all those who have been so kind to my dear wife as well as to myself. I die in the assurance of God’s forgiveness. J.A. Coleman.”

At 8.00am on the morning of the execution, fish vendors at the city market closed their doors for five minutes and the gas lights were dimmed in respect for a fellow fisherman.

After Coleman’s execution, newspaper reporters were denied admission to any future executions in the State. This came about in a letter to the newspapers in 1909 from the Sheriff’s department. At future executions only officials, police and Justices of the Peace were to be admitted. Members of the press were only permitted to attend the Inquest.

Coleman’s age was 58.

Constable Ring was 38.

Constable Ring left a wife and a young child. He is buried alone, due to the Coroner raising serious questions as to why policemen were often not carrying a firearm for protection.

The Police Department purchased new weapons for distribution throughout the force when it was found that only one revolver was kept at the Glenelg police station.

Coleman was executed at 8.00am on 2 July 1908 and buried in the Gaol in ”Murderer’s Row”.

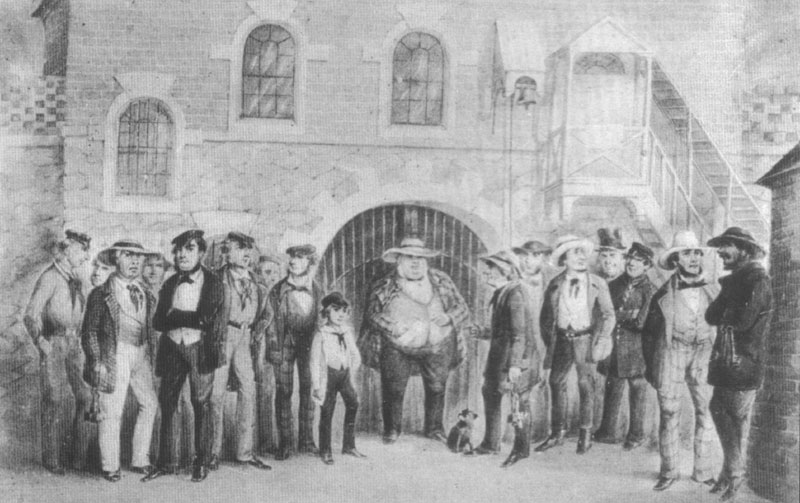

A Picturesque Penitentiary – 1878

By an Eye Witness – 1878.

“What I have seen permit me to relate.”

There is a mystery about a prison too which is not without its effect. The high walls alone suffice to create a thousand conjectures. We wonder as we pass, what events are occurring behind those barriers of brick and mortar, what the beings are like who are producing the measured ‘clink clink’ which falls in rhythmic sounds upon our ears. The interest which all this excites is perhaps a morbid one, but it is none the less a healthy interest, nor indeed a rational one, yet if the prison element is not popular with the millions let me never read Miss Radcliffe again.

I would not have it thought however that I am about to unfold a fearsome tale in this article far from it. The pen and ink sketch I shall make of a prison will be executed with the lightest hand imaginable, there shall not be a shudder in the dozen paragraphs, nor liberal asterisks in the whole article. Let me now with the daintiest of crow quill and the rose coloured ink proceed to sketch my paradigm.

It was shortly after 10.00am one bright sunshiny morning that I drew near H.M.Gaol, I had walked along the railway line marking the pretty effect of the suns rays upon the ornamental brickwork of the building. A number of prisoners were at work in the plantations skirting the railway, but I could not perceive a single warder amongst them.

When within a stones throw of the gaol, a prisoner started up from behind a fence and shouted, “Have you got a bit o’baccy’ on yer old son”. Not deeming it safe to comply with this request, I walked on a few steps, when another broad arrow emblazoned gentleman called out from behind a bush, “Sling us a few strikes (matches) I’m dying for a draw”. At this moment a warder appeared on the embankment, upon which the prisoner commenced doing something with a hoe at a great rate.

I then enquired of the officer the proper entrance to the prison. “Vat for you vent to go into de-shale?” he enquired without directing me. l briefly satisfied him. “You go roun-de little fence-dat bring you, den you ask for Mr Howlah (Howell), der keeper an…”.

Wearying of this Teutonic warder, I straightway crossed a paddock where two prisoners were engaged in haymaking, and going through a small wooden gate found myself facing the main entrance.

Finding the gate of the gaol, strange to say, open, I entered, and found myself in a highly ornamental lobby, to the left of which was a room labelled ‘office’ and to the right another ticketed ‘Waiting room’ while at the end, bathed in a flood of sunshine, stood a stout warder, bearing in his hand a brobdiganagian key (large).

In answer to my questions he informed me that the whole of the clerical work of his establishment is performed by his son and himself, no prisoner being allowed to look into the books on any pretence whatever.

Mr Howell himself impressed me favourably, he is evidently the right man in the right place, and yet he is a post.

After many years of hard study he has almost mastered the mysteries of iambics, trochees, dactyl. He can as Touchstone says “Rhythm you in your true butter woman gallop”.

This is very pleasing, more especially as Mr Howell is an admirable supervisor of the establishment under his charge, enables mankind generally to be able to testify that he unites with his poetic fire the invaluable desiderata of sound common sense, and much practicable knowledge of the art of convict government.

Her Majesty’s Gaol Adelaide, forms a semi-circle, and is divided into 5 yards in each of which is constructed ‘wings’ containing cells for the housing of prisoners. These cells are all over 12 feet in height, and are beautifully clean and admirably ventilated.

Each wing is provided with cells set apart for sick prisoners, ie those suffering from the DTs, these rooms are fitted with an electric bell, which on being pressed by the occupant rings a bell in the corridor where the sentry stands and exhibits upon a dial the number of the cell in which assistance is required. This arrangement common in most hotels, is to the last degree useful and ingenious.

The first yard I entered was number 5, this is set apart for prisoners whose sentences are from 3-6 months. No classification is unfortunately possible here although it is manifestly desirable that an alteration should be made in this respect.

This yard contains 2 wings A-B in the former there are 38 cells and in the latter 14, both yard and out buildings showed signs of cleanliness, neatness and order.

Our next point of inspection was the trial yard number 4, here a number of men were wearily pacing to and fro, all wearing their own clothes, and very seedy garments they looked.

I was informed that prisoners committed for trial are all compelled to keep their cells, bedding, and persons in the highest state of cleanliness.

Kept apart upon the upper tier of C-Wing were 3 little boys – quite children. 2 of these were in trouble for breaking into a church and the smallest of the trio for forgery.

Isolated as they are from the older offenders there is a chance now of saving these children, but should they be sentenced at the supreme court, and pass a period of their childhood spent up with every phase of crime and degradation, it would require no casting of a horoscope to predict the future of these juvenile delinquents.

In this yard there is a ‘day’ room for the use prisoners and also a sleeping place set apart for blackfellows who peacefully slumber four in a row upon bed boards and discuss the political situation unrestrained by the presence of their white brother.

Number 3, or the debtors yard was next inspected. Each prisoner here is allowed to furnish his cell as he has chosen, and one in particular was arranged in quite a luxurious manner. The bed was a tasty little iron couch fitted with a mosquito net, which was trimmed with delicate pink ribbon. There were also books and a profusion of flowers.

Many of the men in this yard are considered for what is termed ‘fraudulent insolvency’ which in this colony is only looked upon as a civil offence, while both in New South Wales and Victoria men convicted of defrauding their creditors are treated precisely the same as the ordinary felon.

The female portion of the prison consists of 2 yards numbers 1-2, with sufficient number of cells and outhouses.

The female prisoners are under the care of a matron and 2 assistants.

I had the pleasure of being introduced to one of the lady turnkeys, and the impression she left on my mind was that she is admirably adapted by nature for the onerous duties she has to perform.

While the men with a few exceptions are all employed outside the prison, the work assigned to the women, is of necessity performed in their quarters. The labour principally being oakum picking 18 pound per woman per week, or pulling horsehair, which is very dusty business indeed.

The female prisoners are classified with tolerable completeness for instance, those women who are convicted of being ordinary streetwalkers are kept strictly apart from the others, and all work and take their meals together in one room. I was taken to see these prisoners, and I could not help remarking that they did not seem to mind their temporary incarceration a bit.

The women’s workrooms and cookhouse, hospital, are very defective both as regards space and ventilation. Neither is there that extreme cleanliness observable in them which characterizes the cells of the female prison. This is somewhat counterbalanced by the numbers of smartly printed texts with which the walls of these rooms are ornamented, by the lady visitors, one of these, ‘Go not in the way of evil men’ appeared to be peculiarly appropriate if the same extract, only with ‘women’ substituted, were placed in each cell in the male prison, the effect would be very complete indeed.

Having explored the yards, we next directed our attention to the causeway or space between the inner and outer walls of the prison. Here are to be found the male hospital and surgery on one side, and the cookhouse, bathhouse, store, and workroom on the other.

The male hospital is a melancholy place, ill-lighted, ill-ventilated, and to the last extent cheerless and forlorn. There is no resident Doctor in the prison, but the Colonial Surgeon visits the gaol 3 times a week, and is sent for in case of emergency.

This state of affairs seems to me open to serious criticism. There are 125 men and 55 women confined in the prison, and that there should be no Doctor continually on the spot to attend to the sanitary arrangements of the prison appears quite inexplicable. lf economy be intended successive Administrations which have so long sanctioned this state of affairs may be complemented upon having extended thrift to very extreme limits indeed.

While I am upon this subject I may remark that in the gaol it is true that ordinarily the limit of a man’s period of servitude under Mr Howell’s care is 6 months, still that is a very long time for a man to be kept without mental food of any description. This alone would be punishment enough in itself to some men.

The cookhouse is very well adapted for the purpose both architecturally as regards internal fittings. The prisoners are extremely well fed, as the appended dietary scale which I extract from the rules and regulations will abundantly demonstrate.

The dietary scale allowance for the several classes of prisoners are as follows.

No. 1. Hard Labour – l.5 lb. bread, l.5 pound of meat, 1 lb. potatoes, l.lb peas, 1/2 oz Angar, 2 oz rice, 2 oz salt, l oz soap, 1/2 oz tobacco.

No.2. Light Labour – l lb bread, 1/2 pound meat, 1/2 lb potatoes. 1.2 oz tea, 2 oz sugar, 2 oz rice, 1/2 oz salt, 1/2 oz soap, 1/2 oz tobacco.

No.3. Solitary – l.5 lb bread.

Prisoners are only allowed tobacco as a reward for good conduct and industry.

They are strictly prohibited from smoking in any of the buildings, or during the prescribed workhouse.

Having explored the bathroom which is fitted with one bath only, the storeroom a fine airy apartment, and the workroom, about which perhaps the least said the better, we arrived at the residence set apart by an indulgent government for the hangman.

This man was pacing up and down in the shade opposite his room, so he was drawn out for my special benefit. Mr Ellis a giant old man of medium stature clad in a frowsy old coat, a greasy waistcoat, and a pair of inexpressibles which appeared to have been manufactured out of a gigantic long-infused tealeaf. His physiognomy is the very reverse of repossessing.

Imagine a square shaped head surmounted by a shock of dusty hair, some of which hangs over a low forehead, beneath which from out a pair of shaggy brows peeps forth a pair of bloodshot eyes of cruel expression. To these add a prominent nose covered with ‘grog’ blossoms, a short grisly beard, and you have a portrait drawn from life.

The apartment assigned to the hangman is worthy of the distinguished occupant, it is a large room, dark, close, and filthy dirty. About are strewn a variety of bottles, saucepans, and odds and sods and of broken victuals and torn newspapers.

The atmosphere of the place was so offensive that I could not remain in it above a minute. Though old and feeble the hangman is yet I am told, skilful in the execution of his office.

When I was leaving the prison I could not help thinking what a pleasant place it was, and how very much better off a great many of the prisoners must be inside than when they are dependent on their own exertions for board and residence.

Footnote. After this visit there were 2 fires in 2 years next to Ellis’s room which was approximately across from the present day tunnel. Benjamin Ellis lived in the gaol until his death in May 1881. He was buried by the government contractor at West Terrace, just of Road 5.

With Acknowledgement to the Adelaide Observer for this short story.