By an Eye Witness – 1878.

“What I have seen permit me to relate.”

There is a mystery about a prison too which is not without its effect. The high walls alone suffice to create a thousand conjectures. We wonder as we pass, what events are occurring behind those barriers of brick and mortar, what the beings are like who are producing the measured ‘clink clink’ which falls in rhythmic sounds upon our ears. The interest which all this excites is perhaps a morbid one, but it is none the less a healthy interest, nor indeed a rational one, yet if the prison element is not popular with the millions let me never read Miss Radcliffe again.

I would not have it thought however that I am about to unfold a fearsome tale in this article far from it. The pen and ink sketch I shall make of a prison will be executed with the lightest hand imaginable, there shall not be a shudder in the dozen paragraphs, nor liberal asterisks in the whole article. Let me now with the daintiest of crow quill and the rose coloured ink proceed to sketch my paradigm.

It was shortly after 10.00am one bright sunshiny morning that I drew near H.M.Gaol, I had walked along the railway line marking the pretty effect of the suns rays upon the ornamental brickwork of the building. A number of prisoners were at work in the plantations skirting the railway, but I could not perceive a single warder amongst them.

When within a stones throw of the gaol, a prisoner started up from behind a fence and shouted, “Have you got a bit o’baccy’ on yer old son”. Not deeming it safe to comply with this request, I walked on a few steps, when another broad arrow emblazoned gentleman called out from behind a bush, “Sling us a few strikes (matches) I’m dying for a draw”. At this moment a warder appeared on the embankment, upon which the prisoner commenced doing something with a hoe at a great rate.

I then enquired of the officer the proper entrance to the prison. “Vat for you vent to go into de-shale?” he enquired without directing me. l briefly satisfied him. “You go roun-de little fence-dat bring you, den you ask for Mr Howlah (Howell), der keeper an…”.

Wearying of this Teutonic warder, I straightway crossed a paddock where two prisoners were engaged in haymaking, and going through a small wooden gate found myself facing the main entrance.

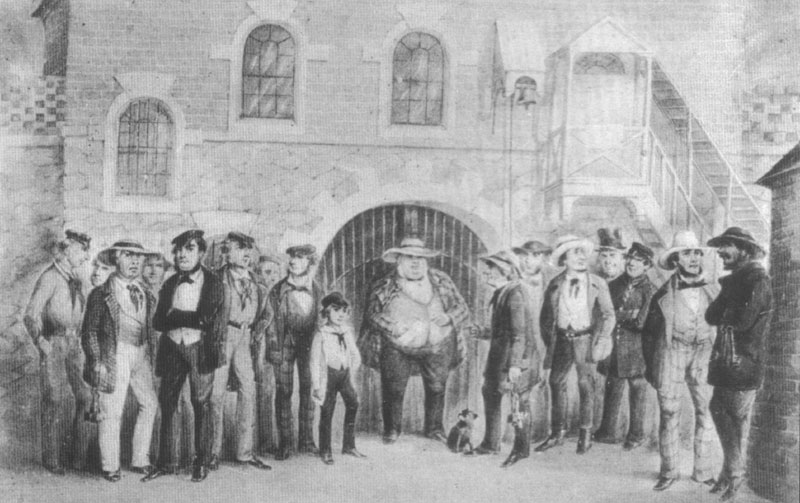

Finding the gate of the gaol, strange to say, open, I entered, and found myself in a highly ornamental lobby, to the left of which was a room labelled ‘office’ and to the right another ticketed ‘Waiting room’ while at the end, bathed in a flood of sunshine, stood a stout warder, bearing in his hand a brobdiganagian key (large).

In answer to my questions he informed me that the whole of the clerical work of his establishment is performed by his son and himself, no prisoner being allowed to look into the books on any pretence whatever.

Mr Howell himself impressed me favourably, he is evidently the right man in the right place, and yet he is a post.

After many years of hard study he has almost mastered the mysteries of iambics, trochees, dactyl. He can as Touchstone says “Rhythm you in your true butter woman gallop”.

This is very pleasing, more especially as Mr Howell is an admirable supervisor of the establishment under his charge, enables mankind generally to be able to testify that he unites with his poetic fire the invaluable desiderata of sound common sense, and much practicable knowledge of the art of convict government.

Her Majesty’s Gaol Adelaide, forms a semi-circle, and is divided into 5 yards in each of which is constructed ‘wings’ containing cells for the housing of prisoners. These cells are all over 12 feet in height, and are beautifully clean and admirably ventilated.

Each wing is provided with cells set apart for sick prisoners, ie those suffering from the DTs, these rooms are fitted with an electric bell, which on being pressed by the occupant rings a bell in the corridor where the sentry stands and exhibits upon a dial the number of the cell in which assistance is required. This arrangement common in most hotels, is to the last degree useful and ingenious.

The first yard I entered was number 5, this is set apart for prisoners whose sentences are from 3-6 months. No classification is unfortunately possible here although it is manifestly desirable that an alteration should be made in this respect.

This yard contains 2 wings A-B in the former there are 38 cells and in the latter 14, both yard and out buildings showed signs of cleanliness, neatness and order.

Our next point of inspection was the trial yard number 4, here a number of men were wearily pacing to and fro, all wearing their own clothes, and very seedy garments they looked.

I was informed that prisoners committed for trial are all compelled to keep their cells, bedding, and persons in the highest state of cleanliness.

Kept apart upon the upper tier of C-Wing were 3 little boys – quite children. 2 of these were in trouble for breaking into a church and the smallest of the trio for forgery.

Isolated as they are from the older offenders there is a chance now of saving these children, but should they be sentenced at the supreme court, and pass a period of their childhood spent up with every phase of crime and degradation, it would require no casting of a horoscope to predict the future of these juvenile delinquents.

In this yard there is a ‘day’ room for the use prisoners and also a sleeping place set apart for blackfellows who peacefully slumber four in a row upon bed boards and discuss the political situation unrestrained by the presence of their white brother.

Number 3, or the debtors yard was next inspected. Each prisoner here is allowed to furnish his cell as he has chosen, and one in particular was arranged in quite a luxurious manner. The bed was a tasty little iron couch fitted with a mosquito net, which was trimmed with delicate pink ribbon. There were also books and a profusion of flowers.

Many of the men in this yard are considered for what is termed ‘fraudulent insolvency’ which in this colony is only looked upon as a civil offence, while both in New South Wales and Victoria men convicted of defrauding their creditors are treated precisely the same as the ordinary felon.

The female portion of the prison consists of 2 yards numbers 1-2, with sufficient number of cells and outhouses.

The female prisoners are under the care of a matron and 2 assistants.

I had the pleasure of being introduced to one of the lady turnkeys, and the impression she left on my mind was that she is admirably adapted by nature for the onerous duties she has to perform.

While the men with a few exceptions are all employed outside the prison, the work assigned to the women, is of necessity performed in their quarters. The labour principally being oakum picking 18 pound per woman per week, or pulling horsehair, which is very dusty business indeed.

The female prisoners are classified with tolerable completeness for instance, those women who are convicted of being ordinary streetwalkers are kept strictly apart from the others, and all work and take their meals together in one room. I was taken to see these prisoners, and I could not help remarking that they did not seem to mind their temporary incarceration a bit.

The women’s workrooms and cookhouse, hospital, are very defective both as regards space and ventilation. Neither is there that extreme cleanliness observable in them which characterizes the cells of the female prison. This is somewhat counterbalanced by the numbers of smartly printed texts with which the walls of these rooms are ornamented, by the lady visitors, one of these, ‘Go not in the way of evil men’ appeared to be peculiarly appropriate if the same extract, only with ‘women’ substituted, were placed in each cell in the male prison, the effect would be very complete indeed.

Having explored the yards, we next directed our attention to the causeway or space between the inner and outer walls of the prison. Here are to be found the male hospital and surgery on one side, and the cookhouse, bathhouse, store, and workroom on the other.

The male hospital is a melancholy place, ill-lighted, ill-ventilated, and to the last extent cheerless and forlorn. There is no resident Doctor in the prison, but the Colonial Surgeon visits the gaol 3 times a week, and is sent for in case of emergency.

This state of affairs seems to me open to serious criticism. There are 125 men and 55 women confined in the prison, and that there should be no Doctor continually on the spot to attend to the sanitary arrangements of the prison appears quite inexplicable. lf economy be intended successive Administrations which have so long sanctioned this state of affairs may be complemented upon having extended thrift to very extreme limits indeed.

While I am upon this subject I may remark that in the gaol it is true that ordinarily the limit of a man’s period of servitude under Mr Howell’s care is 6 months, still that is a very long time for a man to be kept without mental food of any description. This alone would be punishment enough in itself to some men.

The cookhouse is very well adapted for the purpose both architecturally as regards internal fittings. The prisoners are extremely well fed, as the appended dietary scale which I extract from the rules and regulations will abundantly demonstrate.

The dietary scale allowance for the several classes of prisoners are as follows.

No. 1. Hard Labour – l.5 lb. bread, l.5 pound of meat, 1 lb. potatoes, l.lb peas, 1/2 oz Angar, 2 oz rice, 2 oz salt, l oz soap, 1/2 oz tobacco.

No.2. Light Labour – l lb bread, 1/2 pound meat, 1/2 lb potatoes. 1.2 oz tea, 2 oz sugar, 2 oz rice, 1/2 oz salt, 1/2 oz soap, 1/2 oz tobacco.

No.3. Solitary – l.5 lb bread.

Prisoners are only allowed tobacco as a reward for good conduct and industry.

They are strictly prohibited from smoking in any of the buildings, or during the prescribed workhouse.

Having explored the bathroom which is fitted with one bath only, the storeroom a fine airy apartment, and the workroom, about which perhaps the least said the better, we arrived at the residence set apart by an indulgent government for the hangman.

This man was pacing up and down in the shade opposite his room, so he was drawn out for my special benefit. Mr Ellis a giant old man of medium stature clad in a frowsy old coat, a greasy waistcoat, and a pair of inexpressibles which appeared to have been manufactured out of a gigantic long-infused tealeaf. His physiognomy is the very reverse of repossessing.

Imagine a square shaped head surmounted by a shock of dusty hair, some of which hangs over a low forehead, beneath which from out a pair of shaggy brows peeps forth a pair of bloodshot eyes of cruel expression. To these add a prominent nose covered with ‘grog’ blossoms, a short grisly beard, and you have a portrait drawn from life.

The apartment assigned to the hangman is worthy of the distinguished occupant, it is a large room, dark, close, and filthy dirty. About are strewn a variety of bottles, saucepans, and odds and sods and of broken victuals and torn newspapers.

The atmosphere of the place was so offensive that I could not remain in it above a minute. Though old and feeble the hangman is yet I am told, skilful in the execution of his office.

When I was leaving the prison I could not help thinking what a pleasant place it was, and how very much better off a great many of the prisoners must be inside than when they are dependent on their own exertions for board and residence.

Footnote. After this visit there were 2 fires in 2 years next to Ellis’s room which was approximately across from the present day tunnel. Benjamin Ellis lived in the gaol until his death in May 1881. He was buried by the government contractor at West Terrace, just of Road 5.

With Acknowledgement to the Adelaide Observer for this short story.